A decade-old program that provides targeted educational supports for African American males in the Oakland Unified School District has lowered dropout rates and increased graduation rates, new research finds.

With a meaningful reduction of dropouts — 3.6 percentage points — My Brother’s Keeper? The Impact of Targeted Education Supports authors concluded that, particularly among ninth-graders, access to the African American Male Achievement program in the ninth and 10th grades increased the on-time high school graduation rate of black males by about 3 percentage points.

The Stanford-led study notes that Oakland saw graduation rates among black male students increase from 46 percent to 69 percent between 2010 and 2018, which was a faster rate of improvement than the districtwide graduation rate among all students. “Our results also suggest the AAMA program contributed substantially to these gains and might have greater impact if it had a more robust (and similarly effective) presence in 12th grade where dropout rates are substantially higher,” wrote researchers Thomas Dee of Stanford University and Emily Penner of the University of California, Irvine.

Connecting culture and education

Established in the 2010–11 school year among ninth-graders in three comprehensive high schools, the AAMA program has since grown to serve students in many other grades and schools. The program has also thrived despite existing under five different superintendents.

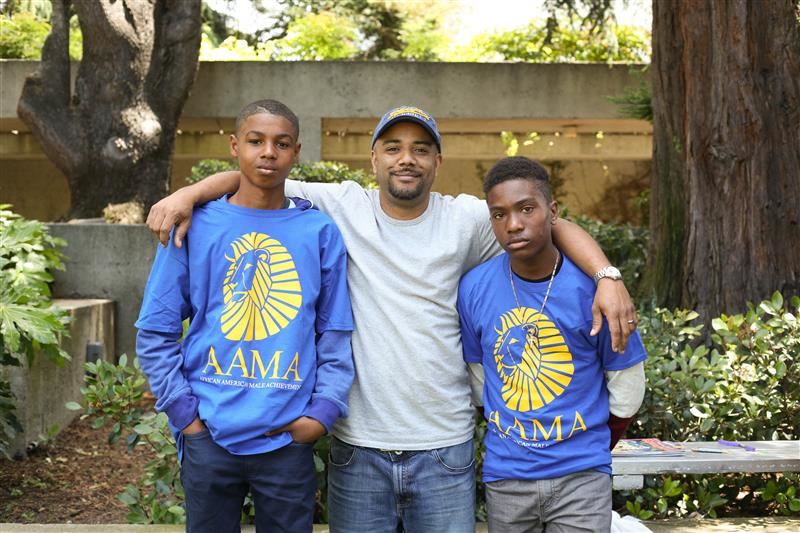

The program’s foundation lies with classes taught by black, male teachers that emphasize social-emotional development, African American history and culturally relevant pedagogy. The program centerpiece, the Manhood Development Program, is a class that meets every day during regular school hours. Course instructors are “carefully selected and trained Black males who have a history of involvement in the Black community and are expected to take on a nurturing, familial relationship with students,” researchers note.

The Manhood Development Program instructors emphasize culturally relevant teaching methods; equip students with “identity resources” to counter negative stereotypes and low expectations of black males; and support a college-going culture through guidance and field trips that emphasize college and career readiness. A 2015 publication, The Black Sonrise: Oakland Unified School District’s Commitment to Address and Eliminate Institutionalized Racism, further examines the program.

Lessons learned and future applications

The City of Oakland’s My Brother’s Keeper plan now prominently features the AAMA as “a leading example of Oakland’s willingness to confront racial equity locally, and be a national model of change.” My Brother’s Keeper, introduced in 2014 during the Obama administration and continuing now as part of the Obama Foundation, partnered with Oakland to support its work.

But despite Oakland USD’s progress and national attention, improvement can take years of effort and culture shifts.

Researchers Dee and Penner noted that while Oakland USD has a long track record of providing new programs for students of color, advocates had long leveled that, prior to AAMA, the district was failing to properly serve black students. The U.S. Department of Education’s Office of Civil Rights agreed with advocates, in 1998 finding the district out of compliance with Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1965. Internally, a 2010 district review found that “past initiatives had done little to transform the experiences, access, or educational attainment” of black males.

The successes and growth experienced in Oakland in the last decade could serve as a model for districts in a state facing persistent opportunity and achievement gaps for students of color. California’s 2018 graduation rate for African American students was 73.3 percent, lagging well behind Asian (93.6 percent) and white (87 percent) students. Further disparities exist in discipline, as African American students were suspended at a rate of 9.4 percent in 2018, nearly tripling the state average of 3.5 percent.

Additionally, the Manhood Development Program’s exclusive use of black, male teachers could lend valuable lessons and practices to state leaders as they look to dramatically increase California’s number of teachers of color. Extensive research has found that all students, not just students of color, benefit from having teachers of color.