By

The combination of stagnant incomes and California’s continually rising housing costs weighs heavily on public school employees across the state. Numerous recent headlines (see Mercury News, San Francisco Chronicle, and NPR, among others) highlight stories of teachers who are struggling to afford housing in the communities where they work, forcing them to take on long commutes or pushing them to leave the education sector altogether. These financial constraints contribute to the ongoing challenges California faces in attracting new teachers and have implications for students as well. Teacher recruitment and retention challenges negatively affect student achievement, especially in schools serving low-income and predominantly Black, Indigenous and People of Color (BIPOC) communities.

California’s local educational agencies own land in every county that could be used to create housing opportunities for their employees. Analysis from our new research report, Education Workforce Housing in California: Developing the 21st Century Campus — developed in collaboration with the Center for Cities + Schools at UC Berkeley, cityLAB UCLA, and the CSBA — sheds light on where and for whom housing affordability challenges may be particularly pronounced among the state’s public education workforce.

Where are California’s teachers struggling to afford housing?

To better understand how school employee salaries across the state stack up against housing costs, we first analyzed where beginning teacher salaries for each school district fall in relation to their county’s median income, referred to as the Area Median Income (AMI). Benchmarking incomes to the local median helps account for geographic variation in the cost of living, including the cost of housing.

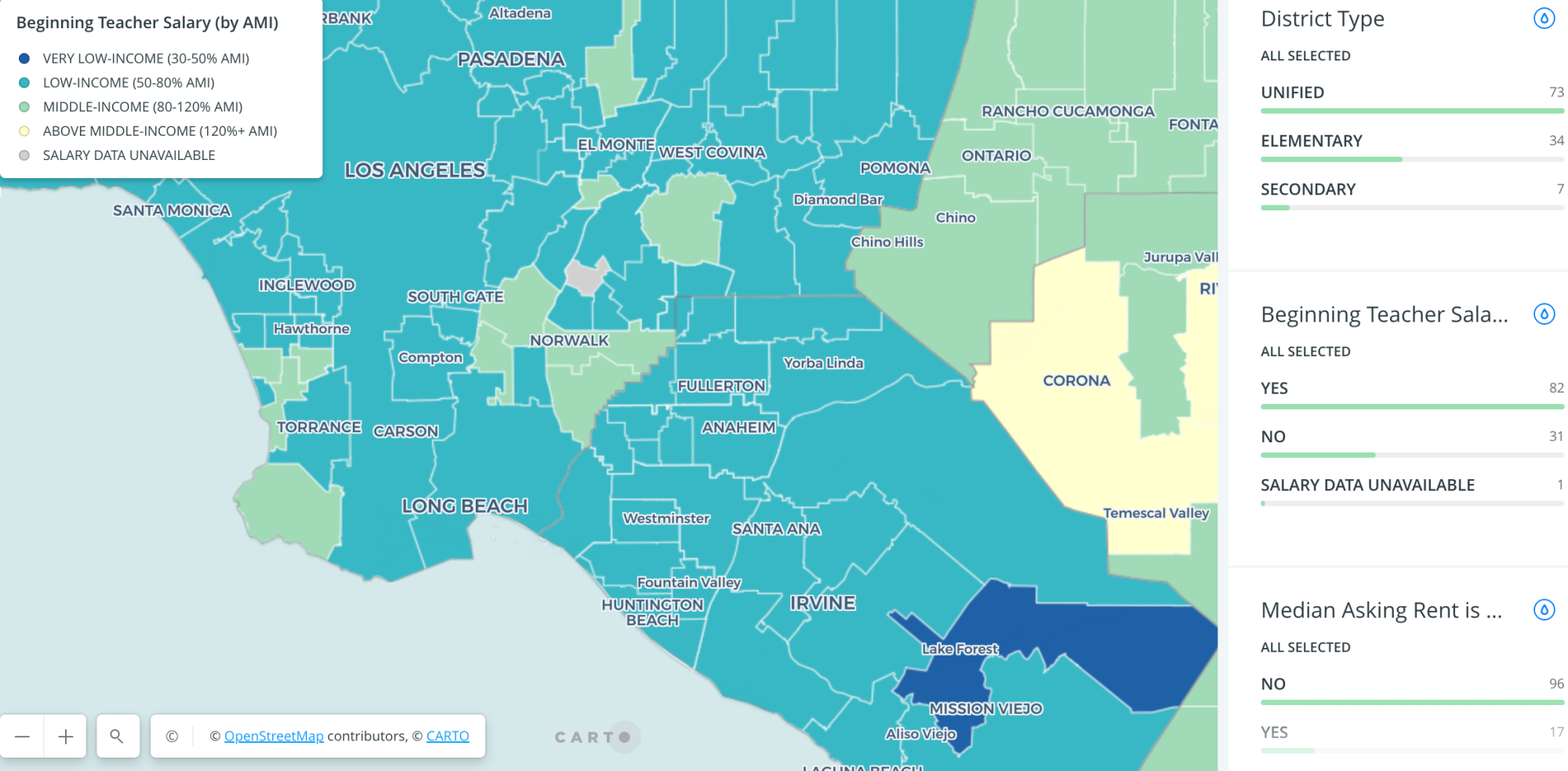

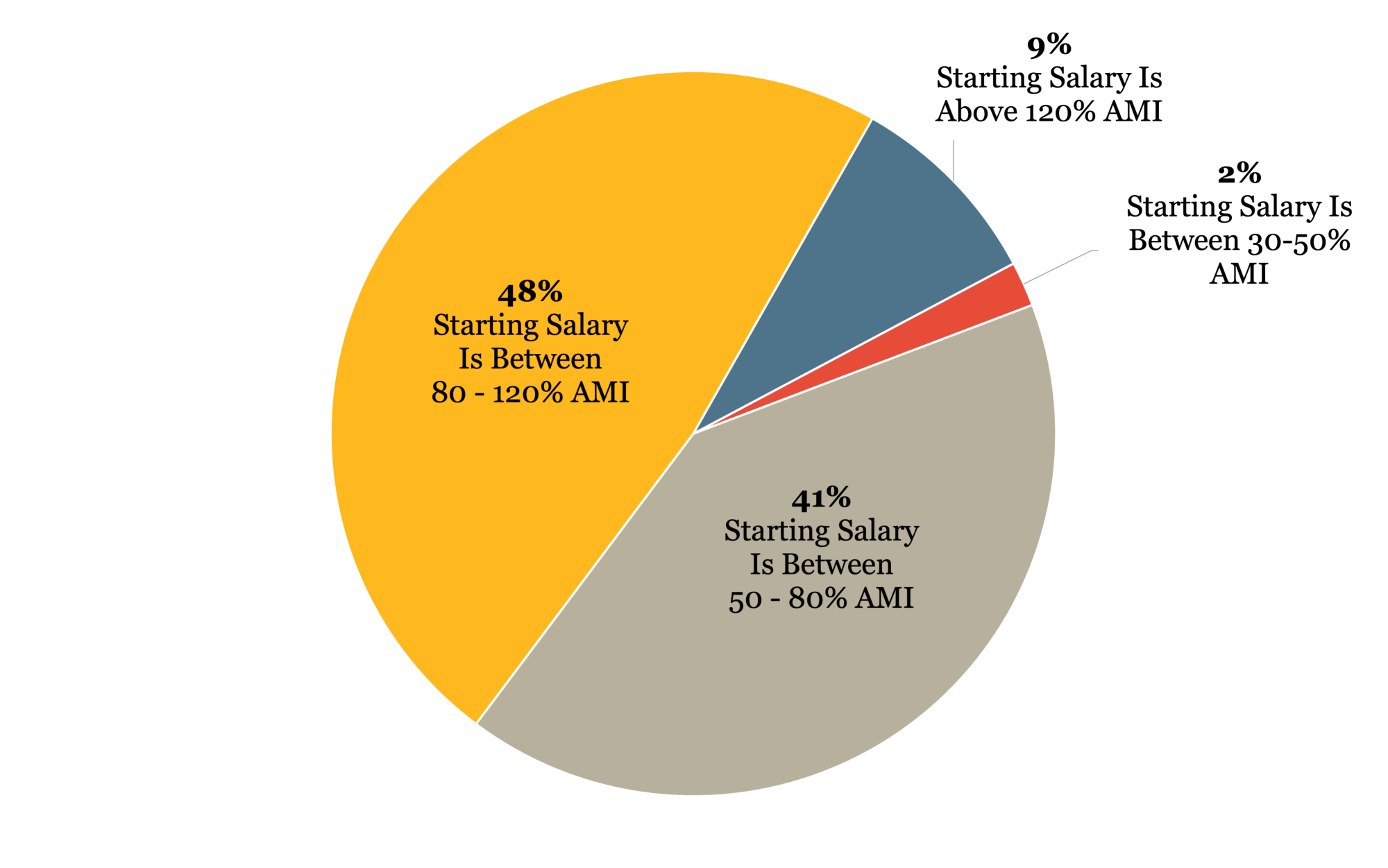

Beginning teacher salaries in California range from $30,000 to $84,500 per year. As Figure 1 shows, 43 percent of districts pay a beginning teacher salary that falls below 80 percent of AMI — a level that qualifies as “low income,” according to the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD). These districts employ nearly 18,000 beginning teachers.

Figure 1. Beginning Teacher Salary by Area Median Income

Source: California Department of Education Certificated Salaries & Benefits data, 2018-2019. The Department of Housing and Urban Development Income Limits data, 2018

These starting salaries translate into very weak purchasing power in many local housing markets, particularly in high-cost areas of the state. Half (52 percent) of California school districts are located in counties where someone earning the beginning teacher salary cannot afford the median asking rent without becoming rent-burdened, meaning that they spend more than 30 percent of their income on housing. This includes 81 districts that pay a middle-income (80-120 percent AMI) starting salary.

For example, Santa Clara Unified offers a starting salary of $73,103, but the median asking rent in Santa Clara County is $2,348, a full $500 above what would be considered affordable for a single-earner with that salary. A beginning teacher at Los Angeles Unified is considered low-income with a salary of $46,587, and cannot afford the Los Angeles County median asking rent of $1,472. For some, even the cost of a studio or one-bedroom unit is out of reach. At San Marcos Unified in San Diego, less than one third (30 percent) of the county’s studio and one-bedroom stock is affordable at the district’s starting salary. For a new teacher at South San Francisco Unified, only 11 percent of studio and one-bedroom units rent at an affordable price.

These housing pressures are most acute in coastal areas, but are of concern in other areas of the state as well. In the Sacramento Valley’s Yolo County, the median asking rent is not affordable for beginning teachers working at five of the county’s six school districts. Rental affordability is also a challenge for new teachers working at certain districts in Riverside County. For example, despite earning what HUD considers a middle-income salary, a new teacher at Desert Center Unified cannot afford the typical asking rent in the county.

What about affordability challenges for non-teaching staff?

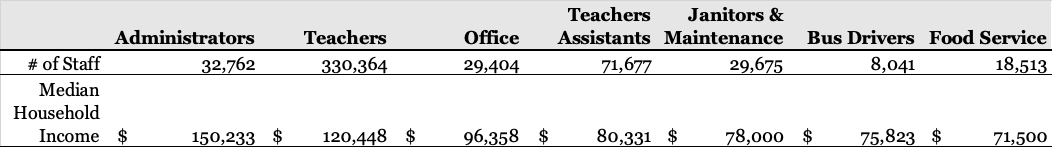

While the focus is often on teachers, many other critical school district staff also struggle with housing affordability challenges. The median household income of office staff, teaching assistants, janitors, bus drivers and food service workers all fall below those of teachers and administrators, as shown in Figure 2. Bus drivers earn a median income of just over $30,000, whereas food service workers on average earn less than half of that.

Figure 2. Median Income by School Employee Type in California

Source: Terner Center analysis of American Community Survey 2018 5-year PUMS

The combination of low incomes and high housing costs leads to high rates of rent burden among school employees. While the rate of rent burden among teachers is significant (31 percent), it is substantially higher for non-teaching employees, particularly teachers assistants (50 percent) and food service workers (55 percent) (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Rent Burden by School Employee Type in California

Source: Terner Center analysis of American Community Survey 2018 5-year PUMS

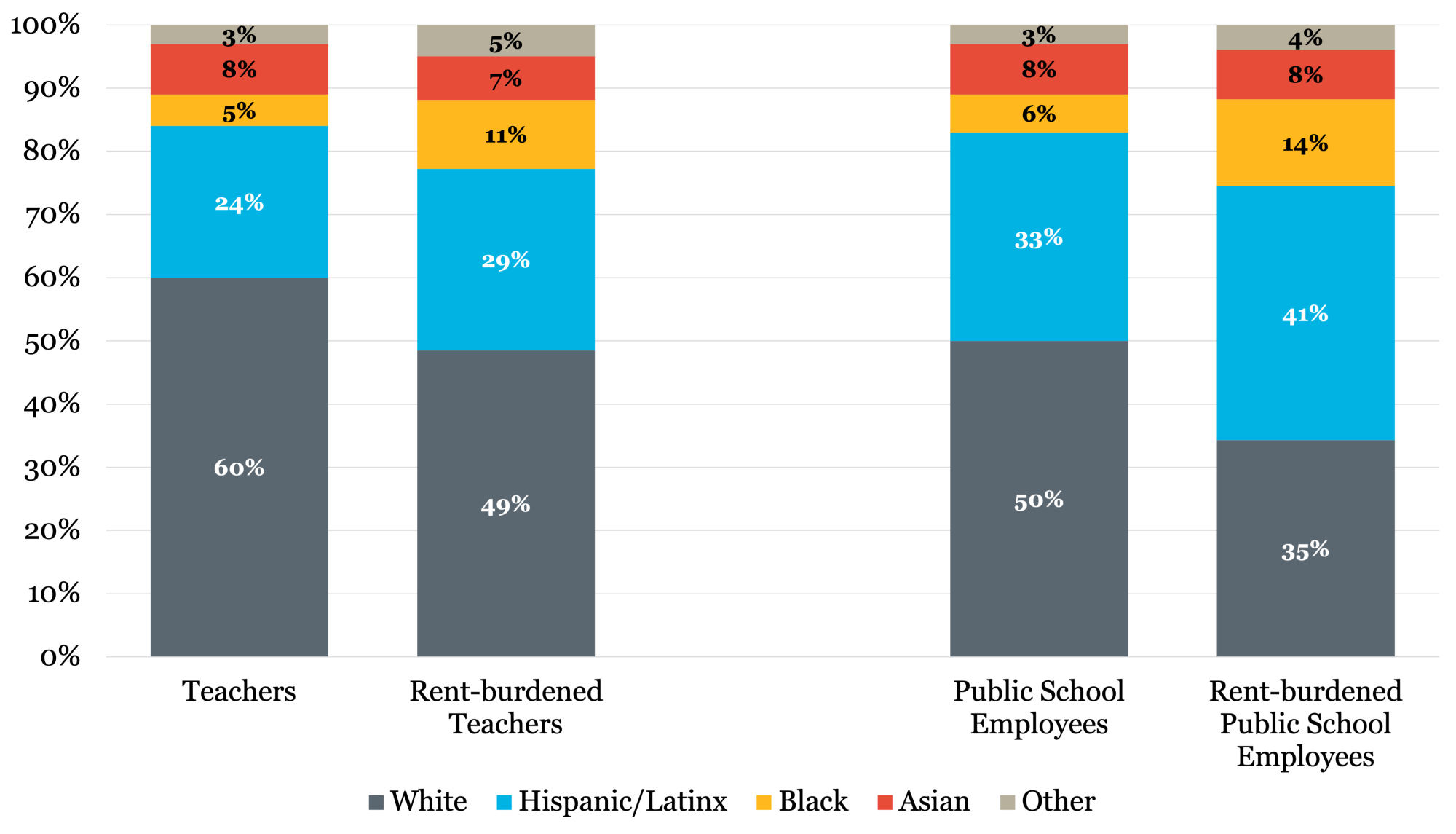

What do housing cost challenges look like for BIPOC employees?

The reality is clear for public school employees in California: housing costs are a formidable obstacle, particularly for early career teachers and non-teaching staff. Employees of color, however, are especially disadvantaged. Teachers and school employees experiencing rent burdens are more likely to be Black and Hispanic or Latinx. For example, despite making up only 6 percent of the public education workforce, 14 percent of rent-burdened school employees are Black. Hispanic and Latinx workers account for one-third of employees in public education, but make up 41 percent of those with rent burdens (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Race and Ethnicity of Public School Employees, by Presence of Rent Burden

Source: Terner Center analysis of American Community Survey 2018 5-year PUMS. The definition of public school employees includes teachers.

These disparities are important to recruiting and retaining diverse teachers. Research shows that students of color, and especially Black students, are more likely to have improved educational outcomes — such as higher test scores and high school graduation rates — when they have been taught by teachers of color and teachers of the same race/ethnicity. Addressing the housing burdens faced by workers of color in the public education system could help districts attract a more diverse teacher workforce. Many districts are already pursuing one solution: leveraging their own land for the provision of affordable housing options for their employees In our new report, we find that a significant portion of public school district-owned land — more than 7,000 properties across 130,000 acres — has potential for housing development. More than half of these properties are located in areas where beginning teachers struggle with housing costs, and more than 40 percent are located in areas likely to be competitive for key affordable housing financing tools. Learn more about where education workforce housing might be best targeted across the state and recommendations for how districts can effectively pursue housing development, in our full report and handbook.

About this research

This is the first in a series of blogs lifting up key findings, resources, and recommendations from our new research report, Education Workforce Housing in California: Developing the 21st Century Campus, which was co-authored with Center for Cities + Schools at UC Berkeley and cityLab UCLA. Developed in collaboration with the California School Boards Association and funded by the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative, this research assesses the need and potential for public education workforce housing strategies in California, utilizing a unique statewide spatial inventory of district-owned properties, employee salary and staffing data, and local housing conditions. This research highlights lessons learned from districts that have built or are pursuing workforce housing, and shows a range of housing design strategies. The report is also accompanied by an illustrated handbook that provides a how-to guide for school boards, administrators and community members to advance this strategy in communities across California.

Shazia Manji is a research assistant for the Terner Center for Housing Innovation.