By Sydney Maves

While California’s deepening housing crisis continues to affect residents across the state, an overlooked sector of California’s workforce — teachers and other employees working in the public school system — are struggling to find affordable housing in the communities where they work (e.g., “Bay Area Housing Prices Fall Hard on School Teachers” by The Mercury News). The result is they are forced to make long daily commutes, or they decide to leave the education profession altogether. Both scenarios are harmful for teachers, schools and, ultimately, students. Add to that the fact that teacher turnover rates are higher in more disadvantaged schools and school districts, there’s a racial justice imperative at play also. There is hope, however. If we can help keep these teachers in the education workforce by providing housing assistance, it may translate into more stable education staff and, in turn, stronger educational outcomes.

What if school districts had the opportunity to build housing for employees and offer them affordable living?

Our new research report, Education Workforce Housing in California: Developing the 21st Century Campus — developed in collaboration with the Terner Center for Housing Innovation at UC Berkeley, cityLAB at UCLA, and CSBA — finds that each and every public school district (also known as a local educational agency or LEA) in California likely already owns land that should be investigated for housing development potential.

Mapping all the properties owned by California’s K-12 public school districts, we find significant land holdings — more than 11,000 properties, totaling 151,500 acres statewide. On the properties that have one or more schools on them, we tallied more than 700 million square feet of buildings.

About 20 percent of these properties (22,122 acres), do not currently have an operating school on them. On these properties, we tallied about 20 million square feet of buildings.

This massive amount of land held in the public domain suggests significant opportunity — in every county and school district across the state — to explore developing workforce housing to support teachers and other public school employees.

Figure 1: Graphic showing areas of opportunity across the state

In this blog, we summarize our findings on potential developability of school district-owned properties in California.

Which properties have potentially developable space?

Of course, the vast majority of these school district-owned properties are being actively used — for schools, athletic fields, bus barns, offices, storage, parking, etc. To assess the amount of potentially developable land on each property, we tallied existing building footprints and the outdoor physical activity, field space, and bus drop-off area recommended by the California Department of Education. Once these necessary spaces were excluded, the remaining land on each property was considered “potentially developable.” Lastly, we dropped from consideration any properties with potentially developable land of less than 1 acre — a size that is likely too small to accommodate housing development.

Figure 2 shows two example school district properties with existing buildings (in blue), sports fields, and parking clearly visible.

Figure 2: Example school district property

In our “potentially developable” determination, we purposefully did not factor in existing on-site parking. Why? Because we feel there are feasible opportunities to reconfigure existing parking and/or reduce parking demand (by introducing VMT mitigation measures) on many of these properties.

Overall, we find 7,068 school district-owned properties with potentially developable land of one acre or more. These properties total more than 75,000 acres statewide, with a median size of 5.9 acres for properties which contain developable land. The median size of potentially developable properties by county varies significantly from anywhere from 2.0 acres in San Francisco County to as many as 12.9 acres in Amador County.

Which properties are located where staffing challenges and housing challenges intersect?

Many of these properties are located in school districts with staffing challenges and in communities with housing affordability challenges. While any available district-owned property has potential for workforce housing, building housing in locales where these two challenges intersect may have increased benefit.

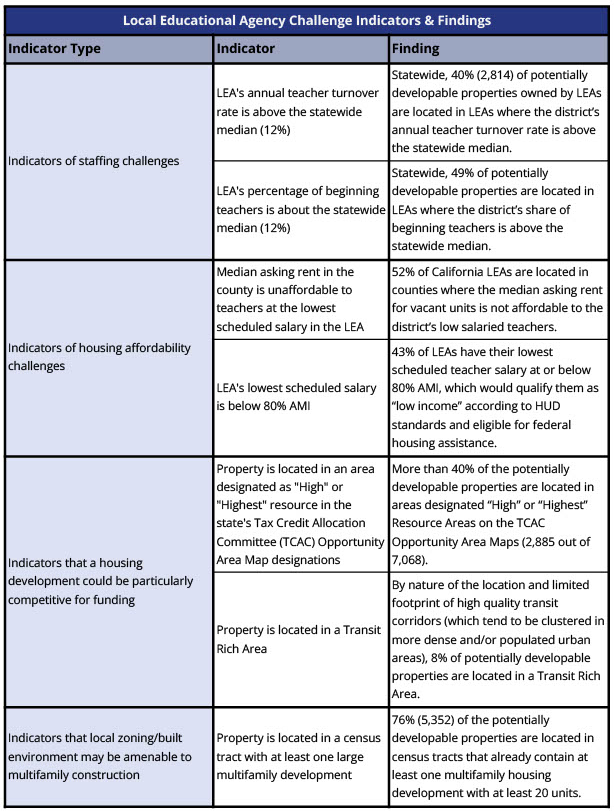

First, we looked at two indicators of staffing challenges: school districts with high annual teacher turnover rates (above the statewide median of 12 percent annually) and school districts where the percentage of beginning teachers is high (above the statewide median of 12 percent).

Next, we looked at two indicators of local housing affordability challenges: where the median asking rent in the county is not affordable to teachers earning the “lowest scheduled salary” (AKA the district’s typical beginning teacher salary), and whether this beginning teacher salary falls below 80 percent of the area median income (AMI). The findings on these four indicators are shown in the table below (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Table of Local Educational Agency Challenge Indicators and Findings Table

Details on our methodology for calculating these findings can be found in the full report.

Which properties are located in places that have additional locational benefits that signal housing opportunity?

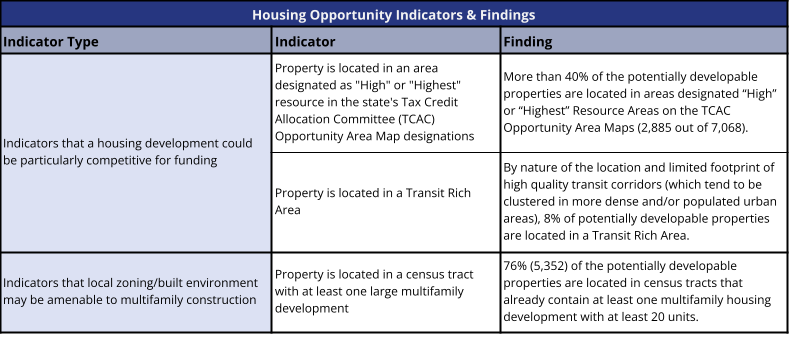

We then examined properties for additional locational benefits that may increase the potential for successful housing development. Specifically, we identified properties that are close to high quality transit and properties in areas with high resource designations, as defined by California’s Tax Credit Allocation Committee (TCAC). Properties in these areas may be particularly competitive for affordable housing funding. We also looked at whether there was existing multi-family housing in the vicinity, which suggests that local zoning is amenable to this type of construction.

Remarkably, 98 percent of the potentially developable properties are characterized by at least one of these three opportunity indicators, as shown in the table below (Figure 4). Almost three quarters (71 percent) are characterized by all of these indicators.

Figure 4: Housing Opportunity Indicators & Findings Table

Details on our methodology for calculating these findings may be found in the full report.

The example map below (Figure 5) shows school district properties (and their existing buildings) in relation to “transit rich areas.”

Figure 5: Example of a school district property in a “transit rich area”

Possibilities are widespread

By activating potentially developable land already owned by school districts across the state, California has an opportunity to strengthen its education workforce, which is a key ingredient to improving school quality for all students as well as promoting a more equitable education system.

Of course, each property will require a careful, on-the-ground assessment to determine its true development potential. But our findings highlight the widespread potential of exploring the possibility of developing workforce housing on properties school districts in California already own.

Moreover, our research finds that development opportunities are not dependent on a public school district’s geographic size. There are significant opportunities for both large and small public school districts across the state to develop workforce housing at a scale which meets their unique needs.

In fact, two school districts have already built teacher workforce housing: Santa Clara Unified and Los Angeles Unified. Casa del Maestro (Figure 6) is one such example in Santa Clara Unified. Casa del Maestro, which contains 40 units, was developed as a way to house beginning teachers while they build equity to purchase their own home. And teachers have liked this resource — roughly 80 percent of tenants have stayed full term. It’s also clear that more school districts are becoming interested in developing workforce housing. In our research, we found 46 school districts that are pursuing projects on 83 sites statewide. Our research highlights significant opportunities for other school districts to consider workforce housing development too.

Figure 6: Casa del Maestro education workforce housing

Taking advantage of the opportunity to build workforce housing on school district-owned land in California will require many pieces to come together — creative thinking, community planning, and, of course, financing. While local school districts will be the drivers of local projects, state agencies – and changes in state policy – will be needed. In our next blog, we’ll dive into the role of state-level action to support local innovation on educator workforce housing.

About this research

This is the second in a series of blogs lifting up key findings, resources, and recommendations from our new research report, ‘Education Workforce Housing in California: Developing the 21st Century Campus’. Read our first blog, STRUGGLING TO LIVE IN THE COMMUNITIES THEY SERVE: HOW HOUSING AFFORDABILITY IMPACTS EDUCATORS AND SCHOOL EMPLOYEES IN CALIFORNIA here. Developed in collaboration with the Terner Center for Housing Innovation at UC Berkeley, cityLab UCLA, and the California School Boards Association, this research assesses the need and potential for public education workforce housing strategies in California, utilizing a unique statewide spatial inventory of district-owned properties, employee salary and staffing data, and local housing conditions. This research highlights lessons learned from districts that have built or are pursuing workforce housing and shows a range of housing design strategies. The report is also accompanied by an illustrated Handbook that provides a how-to guide for school boards, administrators, and community members to advance this strategy in communities across California.

Sydney Maves is a graduate student researcher at UC Berkeley’s Center for Cities+Schools.